Exploring Society: Innovations and tech advancements impact on society.

Introduction and Outline: Why Technology Now Shapes the Story of Society

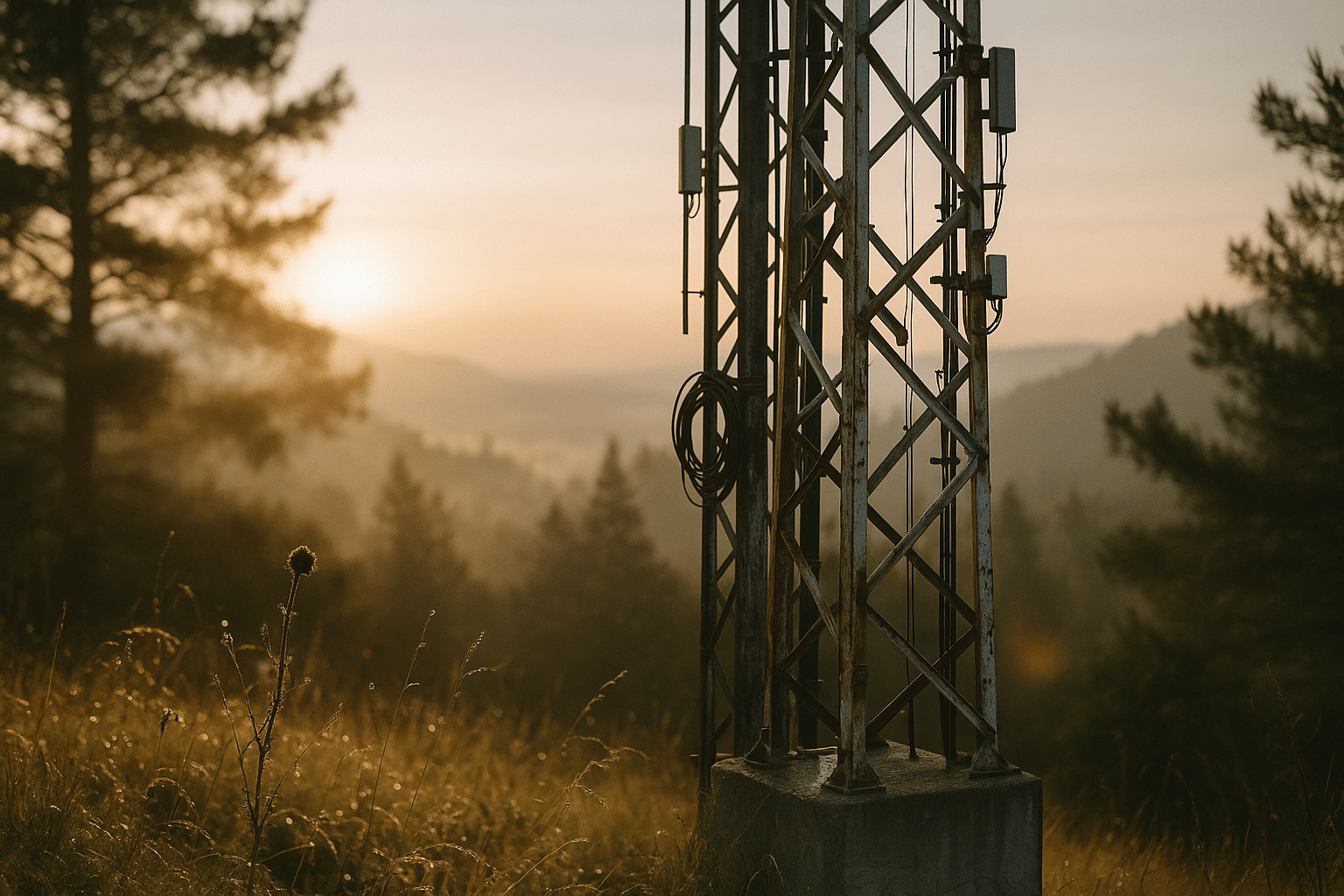

Walk through any neighborhood at dawn and you can hear it—the low hum of servers in a local office, the quiet ping of a delivery scanner in a passing van, the glow of a home router blinking like a lighthouse. Technology is not a separate chapter from society; it is the ink that now runs through each page. From how we learn and work to how we vote, care for one another, and tell stories, digital systems are rewiring habits and expectations. This article explores how innovations reshape social life, why their impacts differ across communities, and what choices can steer those impacts toward inclusion, resilience, and shared prosperity.

Below is a brief outline of the journey ahead, followed by in‑depth sections that expand each point:

– Mapping the terrain: how tech diffuses through daily life and why timing, access, and trust determine social outcomes

– Work, learning, and inequality: productivity gains, skill gaps, and the realities of displacement and new opportunities

– Civic life and institutions: information ecosystems, public services, and the delicate balance between openness and safeguards

– Culture, identity, and well‑being: connection, belonging, and the mixed evidence on screen time and mental health

– A practical compass: principles and actions for individuals, communities, and policymakers to guide innovation toward public value

Relevance is the reason for this conversation. About two‑thirds of people worldwide are online, and the share of devices per household has climbed steadily over the past decade. New tools automate routine tasks, amplify creative work, and compress distances. Yet these gains are uneven. A household’s bandwidth, a worker’s digital skills, or a school’s device policies can determine whether technology widens or narrows opportunity. As a result, societal outcomes turn on choices: what we build, what we regulate, what we teach, and what we choose not to deploy.

What follows blends research‑backed insights with clear, real‑world examples. The aim is practical clarity rather than hype—enough nuance to avoid overstatements, enough concreteness to inform action. If society is a living network, technology is the current: powerful, invisible, and, when guided with care, capable of lighting more than it burns.

Work, Learning, and Inequality: Productivity Gains, Skill Gaps, and Shared Prosperity

In workplaces across sectors, innovation has become less about replacing entire jobs and more about reshaping tasks. Multiple labor studies estimate that a notable fraction of activities within common roles—often in the range of one‑tenth to one‑third—can be automated or augmented with current tools. This “task remix” changes job quality as much as job counts. When routine, repetitive steps are handled by software, remaining tasks tend to emphasize judgment, collaboration, and empathy. The result can be higher productivity and, in some settings, greater job satisfaction. Yet the same shift can compress wages for roles built mostly around routine work or leave workers exposed if training and transition support lag behind.

Education adapts in parallel. Short, stackable learning—modular courses, project‑based credentials, and hands‑on labs—now complements traditional degrees. Learners can simulate complex systems on inexpensive hardware, assess progress in real time, and collaborate asynchronously across time zones. These gains are substantial, but they are not automatic. The quality of instruction, the design of assessments, and the ability to practice skills in authentic contexts determine whether technology enhances learning or simply digitizes old habits.

Consider three practical dynamics shaping equity:

– Access: Reliable connectivity and devices remain unevenly distributed. Rural communities, low‑income households, and learners with disabilities face barriers that can blunt otherwise promising programs.

– Skills: Digital literacy now overlaps with core literacy. Comfort with search, data basics, privacy settings, and collaborative tools increasingly influences employability and civic participation.

– Transitions: Workers displaced by process changes need time, income support, and targeted retraining to pivot into roles that use their experience in new ways.

Evidence from training pilots shows that targeted upskilling—focusing on specific tools and tasks rather than abstract theory—can accelerate wage recovery after displacement. Similarly, apprenticeships that integrate classroom and on‑the‑job learning often deliver durable gains, especially when local employers help shape curricula. On the employer side, clear job architectures and transparent pay bands help workers see paths forward as tasks evolve.

Comparing trajectories, regions that pair broadband expansion with community‑based learning hubs tend to convert connectivity into opportunity more reliably. Where access expands without guidance, gaps can widen: those with strong skills surge ahead while others fall further behind. The takeaway is straightforward but powerful. Productivity improvements become social progress when paired with three ingredients: inclusive access, relevant skills, and intentional transition support. Without them, the same technologies risk reinforcing pre‑existing inequalities.

Civic Life and Institutions: Information Ecosystems, Public Services, and Trust

Democratic life depends on credible information, accessible services, and fair rules. Technology influences all three. Personalized feeds can enrich public debate by exposing people to local issues, niche expertise, and community alerts. They can also fragment the conversation, creating narrow corridors where rumors travel faster than corrections. Several large‑scale analyses have found that sensational falsehoods can spread more rapidly than measured updates, especially during high‑stakes events. The implication is not technological determinism but design realism: the choices behind ranking, recommendation, and reporting systems shape what communities believe and how they act.

Public services are also digitizing—identity verification, benefits enrollment, health scheduling, transit planning, tax filing. When these systems are reliable, accessible, and privacy‑preserving, they reduce friction and expand inclusion. For example, remote identity checks can help residents in distant towns access essential services without costly travel. However, poorly implemented systems can exclude people who lack compatible devices, have limited literacy, or face language barriers. Performance disparities—such as higher error rates for certain demographic groups in automated decision tools—raise additional fairness concerns.

Balancing openness and safeguards requires practical governance tools:

– Transparency: Plain‑language explanations of how automated systems affect eligibility or prioritization, including ways to contest decisions.

– Data minimization: Collect only what is necessary, retain it for the shortest feasible time, and give users simple controls to manage consent.

– Independent evaluation: Regular audits for bias, robustness, and security, with results accessible to the public.

– Human oversight: Clear escalation paths where people can review contested automated outcomes and correct mistakes.

On the information front, communities benefit from layered resilience: media literacy education in schools, fact‑checking workflows in newsrooms, and civic groups that bridge mistrust by hosting in‑person dialogues alongside digital channels. Measured interventions—like labeling clear satire, slowing the resharing of newly flagged content during crisis windows, and amplifying corrections with context—can reduce harmful spread without silencing debate.

Trust grows when systems work in ordinary moments and remain steady in extraordinary ones. Citizens remember whether a portal stayed available during a storm, whether a health reminder arrived in their language, and whether a contested decision could be appealed. Technology can support that memory for the better—if institutions treat reliability, clarity, and recourse as core features, not optional upgrades.

Culture, Identity, and Well‑Being: Connection With Caution

Digital spaces are social spaces. They host birthday greetings, support groups, neighborhood swaps, and learning circles. They also host jockeying for status, comparison spirals, and the occasional shouting match. Most people now weave online and offline identities together, curating what to share and when to retreat. This blended life has both measurable benefits and meaningful risks.

On the upside, creative tools and low‑cost distribution make it easier than ever to publish music, essays, and short films; find collaborators; and gather feedback. Communities that once struggled to find each other—linguistic minorities, caregivers, migrants, hobbyists—build mutual aid networks and share hard‑won knowledge. Accessibility advances have been especially significant. Screen readers, live captioning, audio descriptions, haptic cues, and voice interfaces open doors for people with diverse abilities. With about one in six people worldwide living with a disability, inclusive design is not niche; it’s fundamental infrastructure for cultural participation.

Risks, however, are real. Research examining heavy social media use shows mixed but notable associations with sleep disruption, attention challenges, and lower self‑reported well‑being for some adolescents. Causality is complex: context, content type, and individual differences matter. What seems clearer is that design choices—endless scrolls, intermittent rewards, and prominent metrics—can amplify compulsive use. Misinformation and harassment can also corrode the sense of safety that communities require to thrive.

Three practical practices help tilt the balance toward healthier cultures:

– Friction by design: Gentle speed bumps—like “are you sure?” prompts before resharing or time‑use reminders—can reduce impulsive behavior without heavy‑handed restrictions.

– Context cues: Clear provenance tags for edited images, citations for claims, and visible community guidelines help users interpret content more accurately.

– Shared norms: Schools, families, and groups benefit from co‑created rules about devices at meals, study times, and bedtime—norms that respect both connection and boundaries.

Importantly, culture is not only what we consume but also what we make. Neighborhood storytelling projects, local archives, and community science efforts show how accessible tools can strengthen place‑based identities. When people move from passive scrolling to active contribution—recording oral histories, translating public information, composing micro‑documentaries—the same networks that sometimes feel overwhelming begin to feel like shared, purposeful space. The message is not abstinence but agency: use technology to extend your voice, not to drown it.

Conclusion and Practical Compass: Turning Innovation Into Shared Progress

Innovation changes society not only by what it enables but by what we decide to do with it. The preceding sections point to a simple arc: productivity gains are within reach, public services can become more responsive, and cultural participation can widen—if we plan for access, skills, fairness, and well‑being. That “if” is where audiences across roles can act.

For individuals and families:

– Establish device norms that protect sleep and attention, especially for children and teens.

– Invest a little time each month learning a new digital skill—data basics, privacy settings, creative tools—small steps compound.

– Favor contribution over consumption at least once a week: post a helpful tutorial, review a local service with specifics, or add a citation to community knowledge bases.

For educators and training providers:

– Align curricula with real tasks: simulations that mirror workplace tools, projects evaluated by practitioners, and iterative feedback.

– Pair connectivity initiatives with mentorship and career navigation so learners translate skills into opportunities.

– Integrate media literacy and civics into core subjects, not as add‑ons.

For employers and community organizations:

– Publish clear job pathways, support transitions with paid learning time, and measure outcomes across groups to catch disparities early.

– Treat accessibility as a first‑order requirement from design to deployment.

– Support local hubs—libraries, maker spaces, community centers—that translate access into agency.

For policymakers and public institutions:

– Build trustworthy digital services with transparency, data minimization, independent evaluation, and human oversight baked in.

– Fund evidence‑based upskilling tied to regional industry needs, and provide portable benefits that cushion transitions.

– Encourage open standards so communities and small organizations can interoperate without costly lock‑ins.

A closing image: society as a vast, living circuit. Wires run under streets and over rooftops; signals flow through them like weather. Technology is the conductor, but we—residents, workers, teachers, builders—are the ones who choose the routes and set the breakers. Aim for systems that are resilient in storms and generous in sunshine. That means designs that include those at the margins, rules that defend fairness, and habits that reclaim attention for what matters most. With that compass, innovation can be not a wave that knocks us off our feet, but a tide that lifts more boats—steadily, deliberately, and together.