Exploring Technology: Innovations and tech advancements.

Introduction and Outline: Technology as a Social Force

Technology is not only a collection of tools—it is a living part of society’s fabric, shaping how we learn, work, care for one another, and govern shared spaces. From the phone in a pocket to the fiber beneath a street, digital systems quietly coordinate daily routines, public services, and entire economies. This interdependence makes it vital to explore technology through a social lens: Who benefits? Who is left out? Which values are embedded in design, and how do they ripple through neighborhoods, classrooms, clinics, farms, and factories?

Consider a simple morning: a parent checks transit times, a student logs into a classroom portal, a nurse verifies a prescription, a grocer watches inventory forecast updates. These moments feel routine, yet they depend on complex infrastructures—networks, standards, algorithms, and energy grids—that people rarely see. When they work, life moves seamlessly; when they falter, social trust and opportunity can fray quickly.

This article follows a practical outline to help readers connect innovations with on-the-ground social outcomes. We start with connectivity as a prerequisite for participation, move through shifts in work and skills, examine learning and information ecosystems, and end with a human-centered path forward.

Outline of the article:

– Connectivity and infrastructure as the new social commons

– Work, automation, and the evolving social contract

– Learning, media, and the information ecosystem

– Civic resilience, ethics, and sustainability in a digital era

– Conclusion with practical next steps for households, educators, organizations, and policymakers

Throughout, the goal is to remain grounded: specific examples, balanced trade-offs, and clear actions. Rather than hype or alarm, we focus on steady, evidence-informed guidance that helps communities choose technologies that reflect their values and widen—rather than narrow—access to opportunity.

Connectivity and Infrastructure: The New Social Commons

Connectivity has become a social determinant of opportunity. Without reliable access to the internet and devices, many essentials—education portals, job applications, health scheduling, and benefits enrollment—become harder to reach. Global estimates indicate that roughly two-thirds of people are online, yet billions remain offline or under-connected due to cost, coverage, or skills. Even where mobile broadband coverage reaches most populations, usage lags because service and device costs are still out of reach for many households, and speeds can be inconsistent during peak times.

Infrastructure is more than signal strength. It includes resilient power, community anchor institutions like libraries and clinics, device repair ecosystems, and local support for digital skills. When storms or heat waves disrupt power or network backbones, the social effects compound: payment systems stall, emergency alerts arrive late, and remote services pause. Planning for redundancy—backup power at community hubs, cached local content for schools, alternative last-mile links—turns technology from a brittle utility into a robust commons.

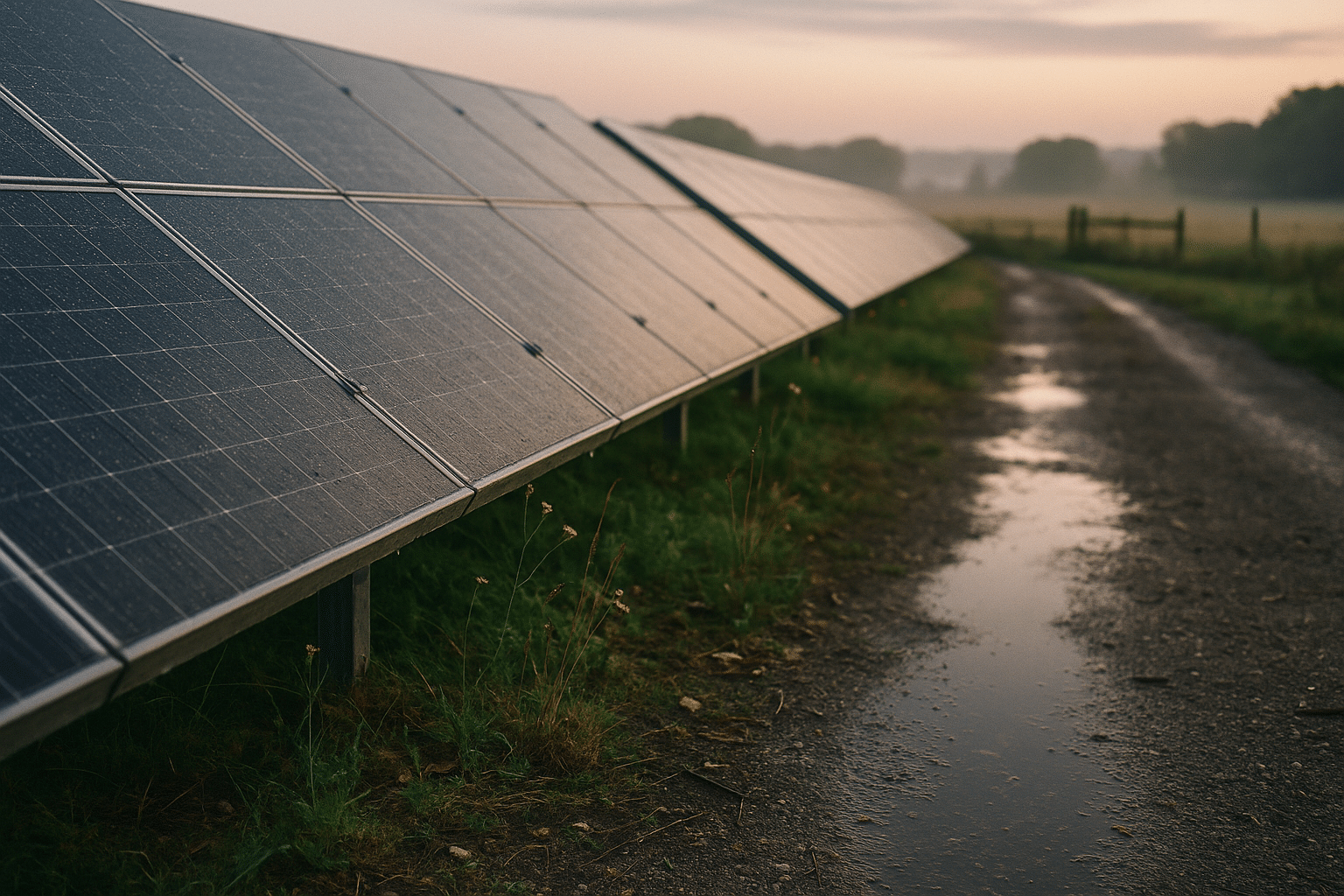

Connectivity quality also shapes social cohesion. Neighborhoods with steady service can coordinate mutual aid, organize local events, and share trustworthy updates. Areas with frequent outages may see frustration and disengagement. For rural communities, connectivity enables telemedicine and precision agriculture; for urban centers, it supports micro-entrepreneurship and transportation planning. The same fiber that carries entertainment carries livelihoods.

Practical levers for inclusion:

– Community Wi‑Fi hotspots near parks, transit, and clinics

– Shared device lending and low-cost repair programs

– Clear, multilingual tutorials on privacy, safety, and online rights

– Local data on coverage, affordability, and outage frequency to guide investment

Affordability remains a core barrier. A small but meaningful drop in entry-level service pricing, or flexible prepaid options, can move households from intermittent to consistent access. Similarly, durable, repairable devices reduce long-run costs. When local governments, schools, and nonprofits coordinate around these principles—open access, redundancy, and repairability—connectivity functions like a public square, widening participation in education, commerce, and civic life.

Work, Automation, and the Evolving Social Contract

Technological change has always reshaped work. What is distinctive today is the speed and scope at which software, robotics, and data-driven systems can reconfigure tasks. Many roles are not replaced outright; instead, tasks within them shift. Routine data entry, scheduling, or standardized reporting can be automated, while human strengths—judgment in ambiguous settings, empathy, creativity, and cross-cultural communication—gain importance.

Studies over the past decade suggest that a significant share of tasks across occupations could be automated or augmented. The precise percentages vary with methods and timeframes, but the pattern is consistent: roles with high routine content face more pressure, while roles requiring complex social interaction or problem-solving are more resilient. In practice, new tasks also emerge—maintaining automated systems, interpreting model outputs, and aligning processes with safety and ethics guidelines.

For individuals and communities, the priority is adaptability. Lifelong learning is less a slogan than a practical shield against volatility. Short, stackable learning pathways—certificates aligned to real tasks—can bridge skill gaps for mid-career workers. Employers can support this shift by recognizing skills evidence beyond traditional degrees and by offering protected learning time.

Elements of a modern social contract:

– Lifelong learning credits that follow the worker across employers

– Portable benefits that travel with workers in nontraditional arrangements

– Wage insurance or transition support during reskilling periods

– Clear standards for transparency and accountability in automated decision systems

Humane adoption of automation matters. When tools are introduced with worker input, measured pilots, and training, productivity and job satisfaction often rise together. When systems are dropped in without consultation, the result can be stress, errors, and mistrust. Small process improvements—like explaining why an algorithm made a recommendation, or allowing human override—help maintain dignity and agency at work.

Local economies can diversify by supporting entrepreneurship tied to emerging tools—repair services, data annotation for specialized domains, safety auditing, and domain-specific training. In this way, automation is not a zero-sum replacement but a catalyst for new roles, provided communities invest in learning pathways and fair transitions.

Learning, Media, and the Information Ecosystem

Education now operates in blended environments where physical classrooms and digital platforms intertwine. This brings reach and flexibility, but also uneven outcomes. Students with stable devices, calm study spaces, and skilled mentors often flourish; those without these supports can fall behind, even if they are highly motivated. Digital equity in education thus means addressing access, quiet space, mentorship, and feedback quality, not only software licenses.

Information quality shapes learning as much as access. Algorithmic feeds can amplify engaging content over careful content, drawing attention toward novelty and away from context. The result is a landscape where credible sources compete with rumors and fabricated narratives. Media literacy is a practical life skill: how to triangulate a claim, check dates and origins, examine incentives, and understand the difference between correlation and causation.

Practical tools for learners and families:

– A simple verification routine: pause, check the source, look for independent confirmation

– Browser features that flag major changes to online pages used for study

– Shared resource lists maintained by libraries and community centers

– Timers and focus modes to reduce distraction during study blocks

Educators can design for attention, not against it. Sequencing tasks—short, focused challenges followed by reflection—helps students build depth without fatigue. Clear rubrics, examples of quality work, and frequent low-stakes practice encourage mastery. Importantly, assessment should reward process and reasoning, not only final answers. When learners explain steps and assumptions, they gain transfer skills that apply outside any single platform.

For public discourse, transparency about how content is ranked or recommended helps communities calibrate trust. Independent audits, open datasets where feasible, and community reporting channels foster healthier information ecosystems. The goal is not to eliminate disagreement—a healthy society needs debate—but to ground debates in verifiable facts and shared methods of checking them.

Civic Resilience, Ethics, and Sustainability in a Digital Era

Digital systems increasingly underpin essential services: water pumps, traffic signals, emergency alerts, and public records. Civic resilience means planning for disruption. Local backup protocols, data redundancy, and clear communication plans ensure that when a system fails, communities can still coordinate. Regular drills—like switching to manual procedures or using alternative channels—turn resilience from a policy into a habit.

Ethical design reflects community values. Privacy-by-default settings, consent that is understandable, and clear data retention limits protect both individuals and institutions. When authorities or organizations deploy analytics or sensors, publishing what is collected, why, and for how long builds trust. In sensitive contexts—schools, health, housing—an extra layer of review helps align innovation with dignity.

Sustainability is part of ethics. Data centers and networks draw substantial energy, and devices require minerals and manufacturing inputs. Meanwhile, discarded electronics are piling up globally, with estimates placing annual e-waste at well over 60 million metric tons and rising. Extending device lifespans through repair, modular design, shared use, and responsible recycling reduces environmental impact while saving money for households and public agencies.

Community-level actions that compound:

– Public “right-to-repair” workshops at libraries and maker spaces

– Procurement policies that favor energy efficiency and repairability

– Open standards that prevent lock-in and lengthen useful life

– Local e-waste collection events with transparent downstream recycling partners

Finally, digital well-being deserves explicit attention. Notifications, infinite scrolls, and rapid-fire updates can fragment attention and elevate stress. Setting shared norms—quiet hours for group chats, response-time expectations at work, device-free zones in homes—helps restore balance. The aim is not retreat from technology but a healthier rhythm between presence and connection.

Conclusion: A Human-Centered Technology Future

Technology’s arc is neither automatically liberating nor inevitably harmful. Outcomes depend on choices made by households, schools, workplaces, and governments. Centering people—especially those at risk of exclusion—yields systems that expand opportunity and resilience.

Practical next steps:

– Households: Map essential digital needs (school, work, health) and align budgets toward stable access and durable devices; create shared norms for attention and privacy.

– Educators: Blend access support (devices, quiet spaces) with media literacy and process-focused assessment; partner with libraries and local organizations for mentorship and maker activities.

– Organizations: Introduce automation with worker input, training, and clear override paths; recognize skills evidence beyond traditional degrees; design privacy-respecting defaults and publish data practices.

– Policymakers: Track local affordability and outage metrics; support open standards, repairability, and energy-efficient procurement; provide portable learning credits and benefits that travel with workers.

Across these domains, three principles guide decisions. First, equity: broaden participation by reducing cost and skill barriers. Second, resilience: design for graceful failure with redundancy and drills. Third, transparency: explain how systems work and how decisions are made. When communities act on these principles, innovations align with shared values rather than dictating them.

The importance of tech in everyday life is clear; the opportunity is to ensure it serves as a public good. With steady investment in connectivity, human skills, ethical guardrails, and environmental care, society can make digital progress feel less like a race and more like a well-marked path—walkable, inclusive, and sturdy underfoot.